John Maynard Keynes is credited with saying,

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

However, there is no definitive evidence that he actually said or wrote it.

Wall Street’s forecasting community (including us) is scrambling both to assess February’s weaker-than-expected batch of economic indicators for January and to reassess the likely near-term negative impact of Trump 2.0.

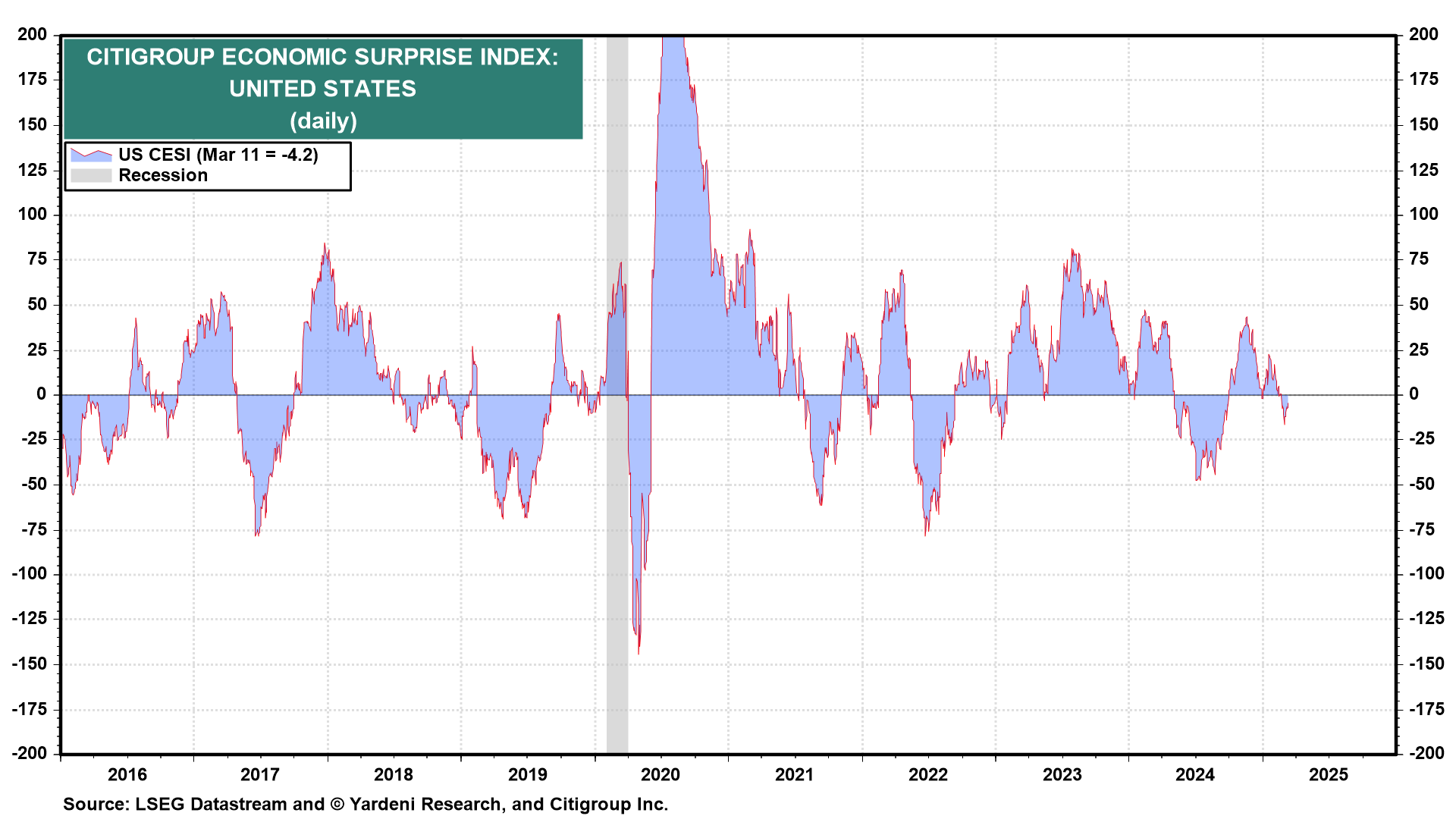

The Citigroup Economic Surprise Index surprised most forecasters during the second half of last year with positive readings (Fig. 1). It has surprised them with slightly negative readings since February 20.

We continue to bet on the resilience of the economy. However, we acknowledge that it is being severely stress-tested now by Trump 2.0’s tariff turmoil and shotgun approach to paring the federal workforce.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is that President Donald Trump wasn’t bluffing or even just exaggerating when he often said during his presidential campaign rallies that he loves tariffs. The widespread assumption was that his constant threat to raise tariffs was mostly a negotiating tool to force America’s major trading partners to lower their tariffs.

However, he also often said that he viewed tariffs as a great way to raise revenues and to force US-based companies to move operations back to the United States.

President Trump talked about tariffs at the Inauguration Day parade held in the Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C. He said,

“I always say tariffs are the most beautiful words to me in the dictionary.” He added that “God, religion, and love are actually the first three in that order, and then it’s tariffs.” That sounded like Trump’s typical bluster, positioning him to make deals to reduce other countries’ tariffs. But, apparently, he meant it: The man loves tariffs. He has even called himself “tariff man.”

On March 7, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said,

“We’re going to make the External Revenue Service replace the Internal Revenue Service.”

In other words, revenues from tariffs will replace revenues from taxes on individuals and corporations. That’s simply dangerous and delusional nonsense. It certainly isn’t passing the sanity test in the US stock market. Consider the following:

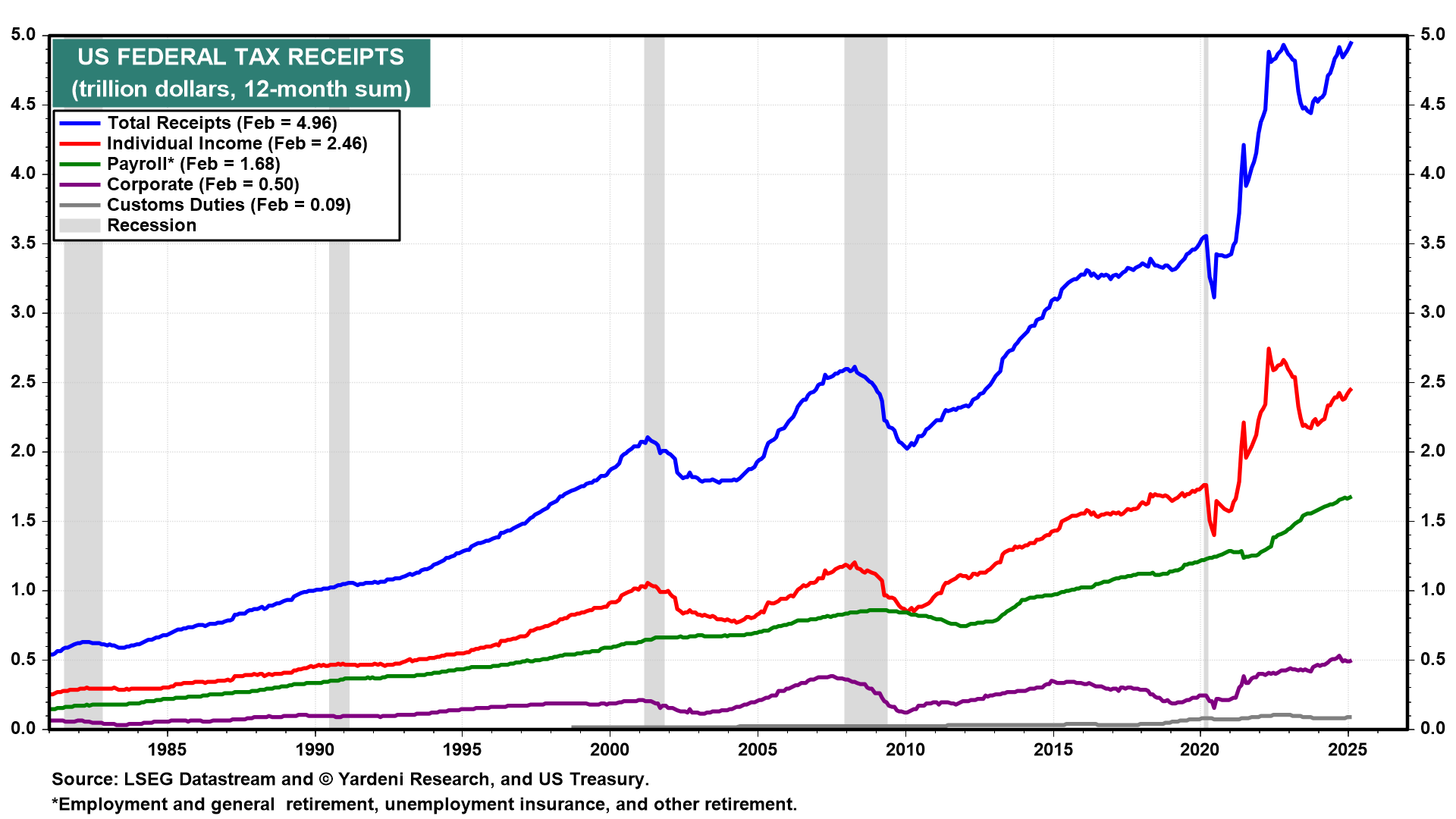

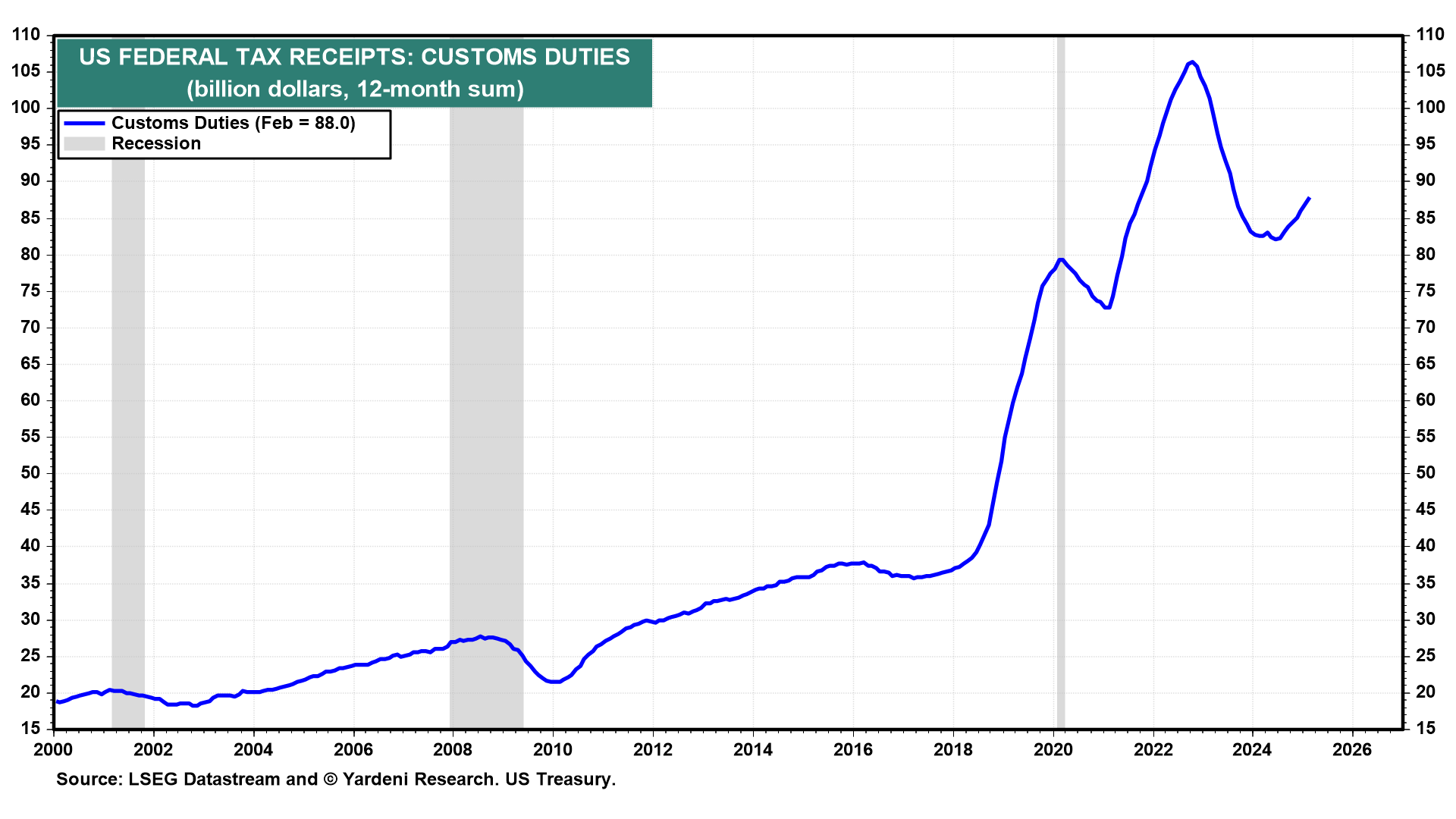

Over the past 12 months through January, federal tax receipts totaled $4.9 trillion (Fig. 2). That included a piddling $87 billion in customs duties (Fig. 3).

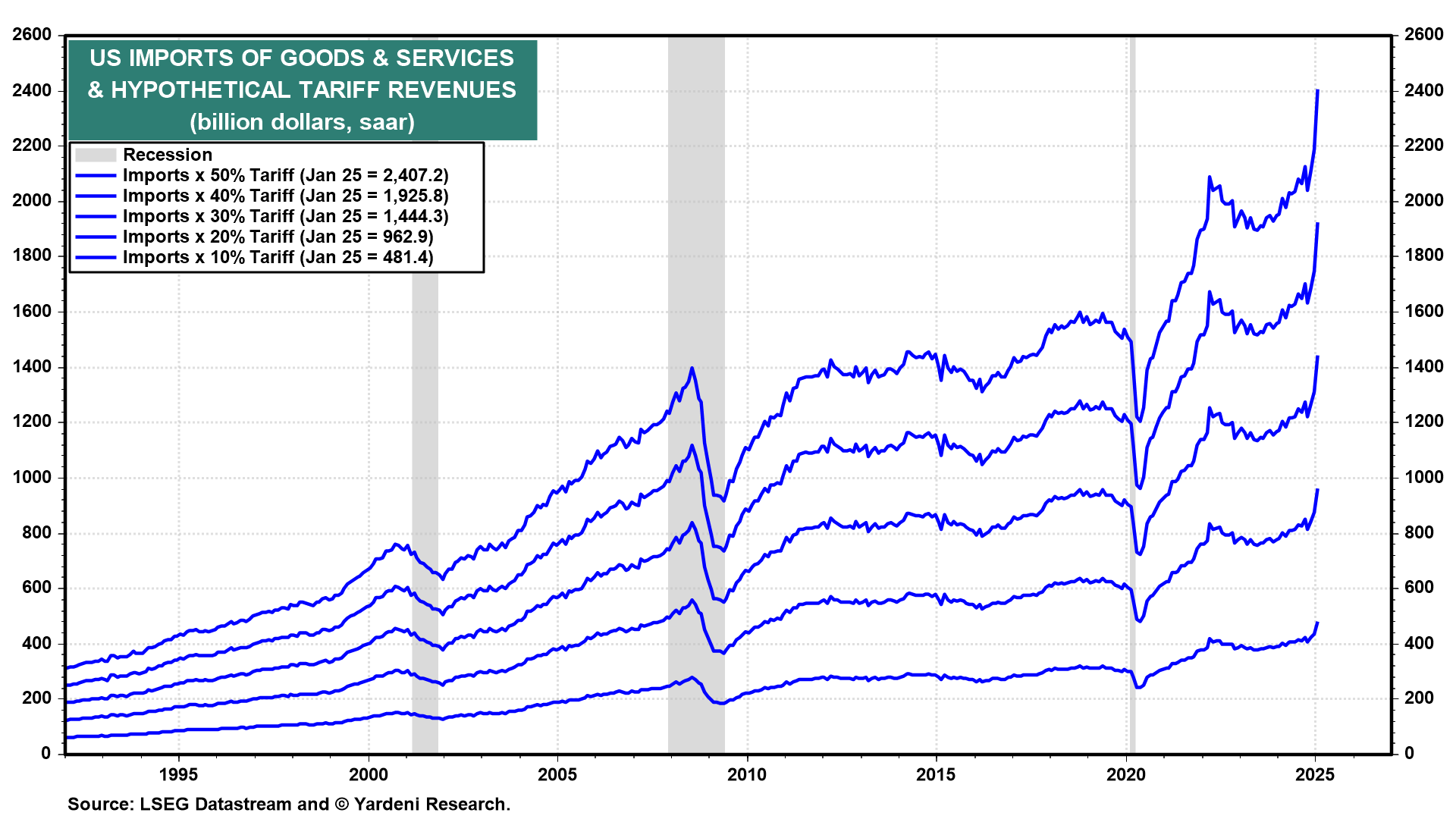

A 20% tariff on all imports including goods and services would raise less than $1 trillion over a 12-month period (Fig. 4). It would take a 100% tariff to raise the $5 trillion necessary to shut down the IRS and replace it with the ERS.

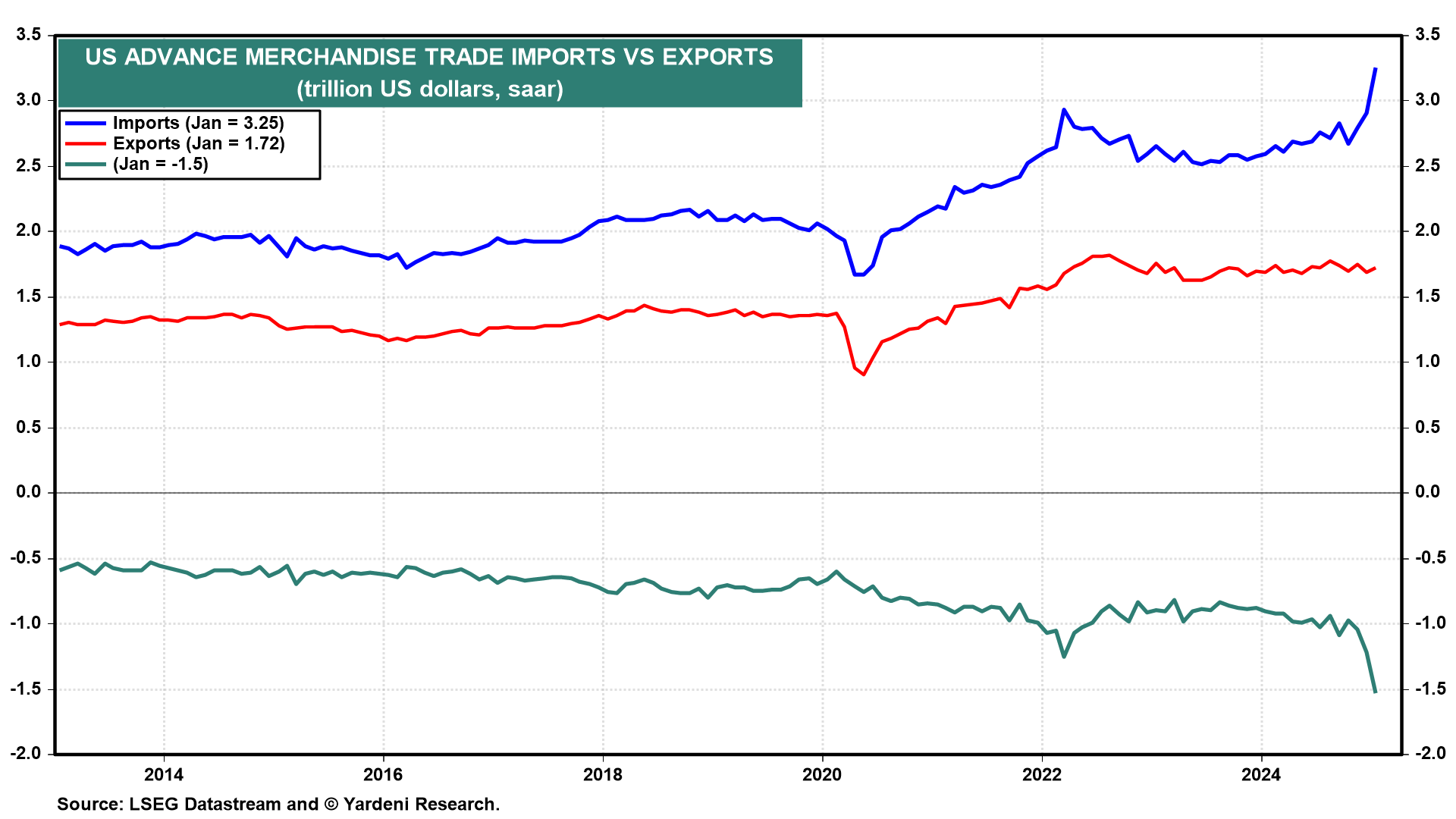

The tariff would have to be even higher if it is imposed on only on imports of goods, which totaled $3.3 trillion over the past 12 months through January—and that includes January’s huge jump inflated by importers’ front-running tariffs, especially of gold bars (Fig. 5).

And that would still not balance the federal budget. To do that, customs duties would have to be much higher to match federal outlays, which were $7.1 trillion over the past 12 months.

Of course, the above assumes that funding the External Revenue Service of America doesn’t instigate a global trade war, which might cause a depression and a collapse of global trade, including US imports.

That is probably a bad and very dangerous assumption since some countries are already retaliating against Trump’s tariffs.

So far, that group consists of just Canada, China, and the European Union. But lots of others may join the fray on April 2, when the US is scheduled to impose reciprocal tariffs.

Tariffs are taxes that are paid by consumers of those goods, importers of them, and/or exporters of the goods. Of the three, consumers are the ones most likely to pay the tax in the form of higher prices.

The tax base of tariffs (i.e., imports) is much smaller than is the tax base that includes personal income and corporate profits. A consumption tax would make more sense as a revenue raiser, since consumption represents the largest tax base.

Our message to the White House: Mr. Trump, don’t build your tariff wall! Tear down tariff walls around the world by negotiating free-trade deals!

Time To Blink?

Given all the above, it isn’t surprising that many forecasters are turning more cautious on the economic outlook. Some are lowering their outlook for and their year-end forecasts for the .

We respect the economists and strategists at Goldman Sachs (NYSE:). That’s because they have often agreed with our outlook for the economy and financial markets. They are data-dependent, as we are. However, it seems to us that they tend to tweak their forecasts faster and more often in response to new data than we do because we tend to stick to our base-case scenarios longer.

So their forecasts occasionally reflect the latest data points sooner than we do. We, on the other hand, tend to question data that don’t support our outlook. More often than not, this approach has worked for us, as subsequent data and/or revisions in the previous data often proved to support our narrative after all. In other words, Goldman’s view tends to determine the consensus outlook. We tend to stray occasionally.

Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. The latest batch of economic indicators released on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday supported our resilient economy scenario with subdued inflation. Nevertheless, we can’t ignore the potential stagflationary impact of the policies that Trump 2.0 is currently implementing haphazardly. Consider the following:

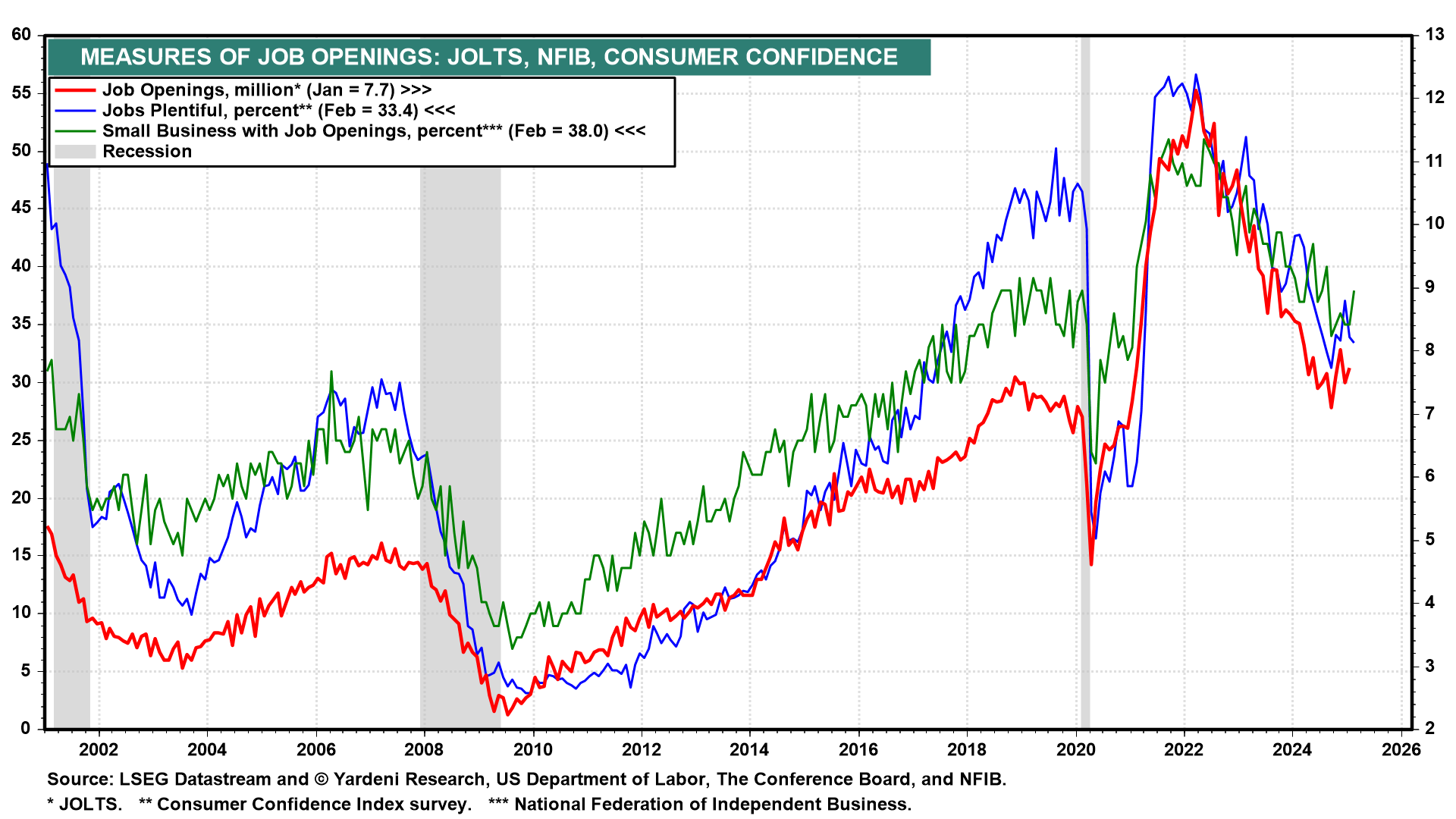

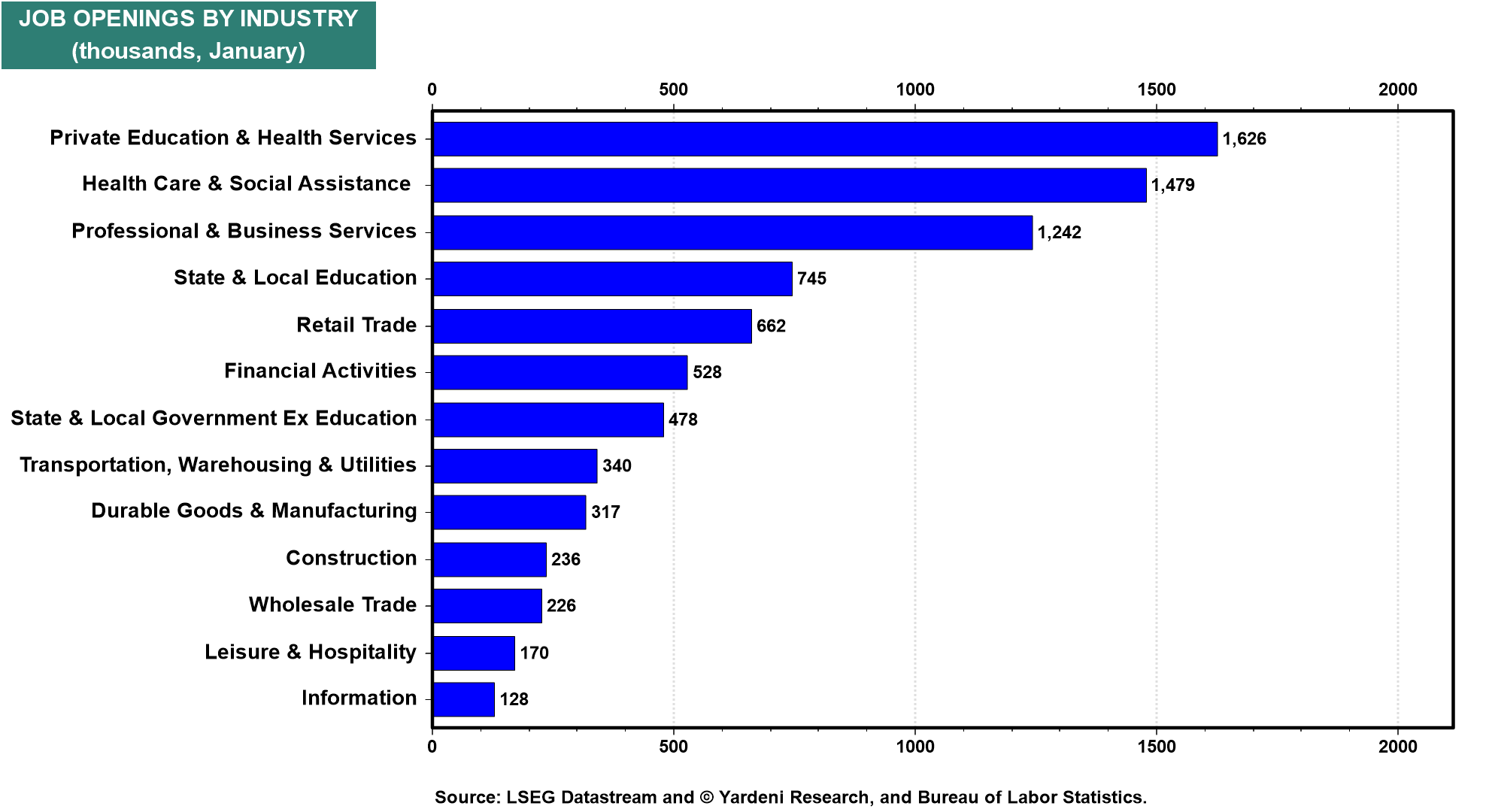

The labor market indicators in Tuesday’s survey of small business owners during February and January’s report provided solid readings on the labor market. Job openings remained relatively ample (Fig. 6). There were even 662,000 job openings in retail trade during January, which should offset some of the concern about the spike of 39,000 announced layoffs in the industry during February (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

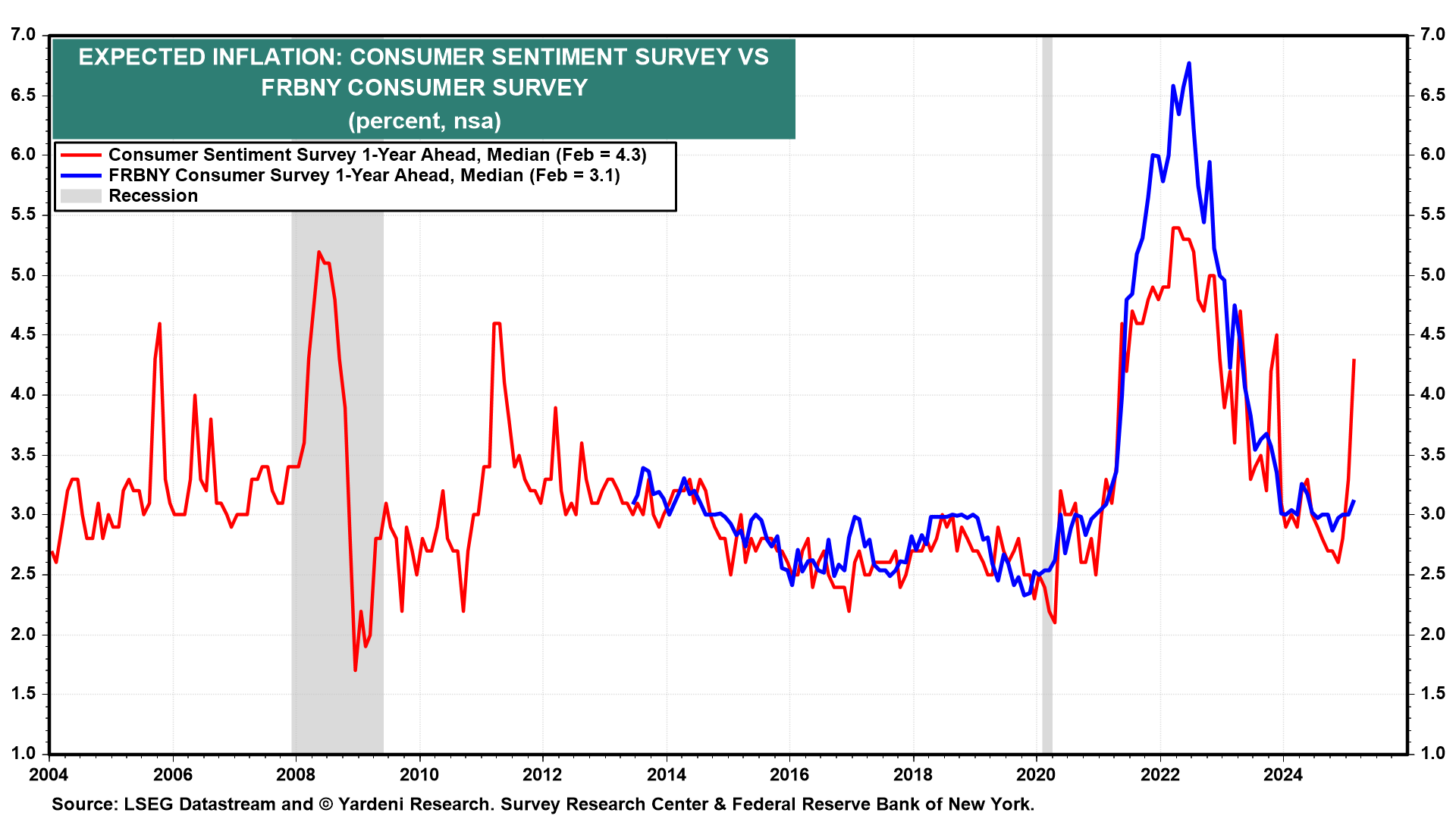

Monday’s report on consumers’ inflationary expectations over the next 12 months released by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York showed a much more subdued response to tariffs during February than did the Consumer Sentiment Index survey (Fig. 9). The former reported the one-year ahead expected inflation rate at 3.1%, while the latter jumped to 4.3% (Fig. 10). February’s inflation rate reported on Wednesday was a bit cooler than expected.

The above are certainly not stagflationary readings.

Yet Goldman’s economists cut their real GDP growth projection for 2025 from 2.4% to 1.7% in response to Trump’s tariffs. That was on Tuesday. On Wednesday, Goldman’s strategists lowered their year-end S&P 500 target from 6500 to 6200.

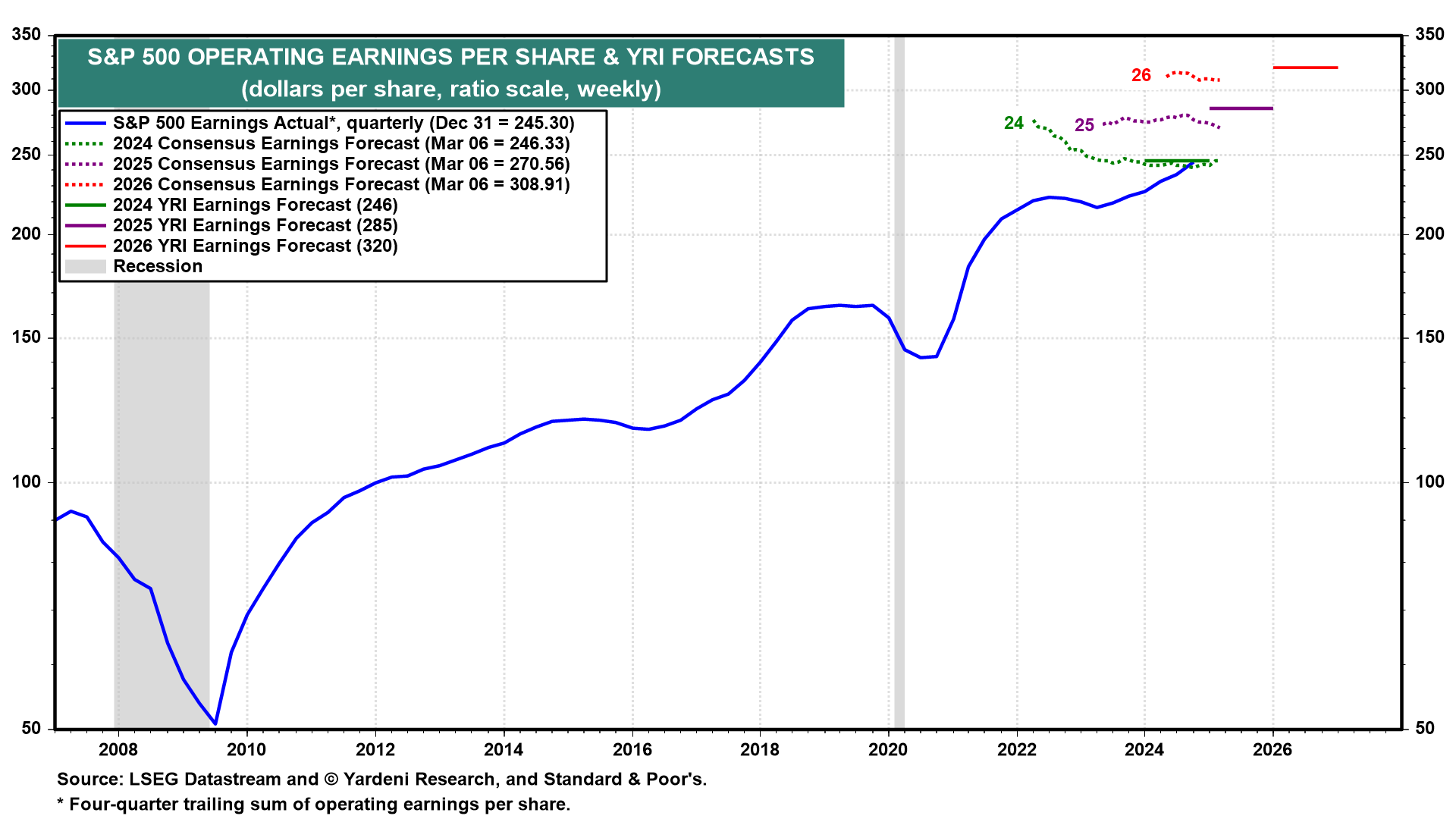

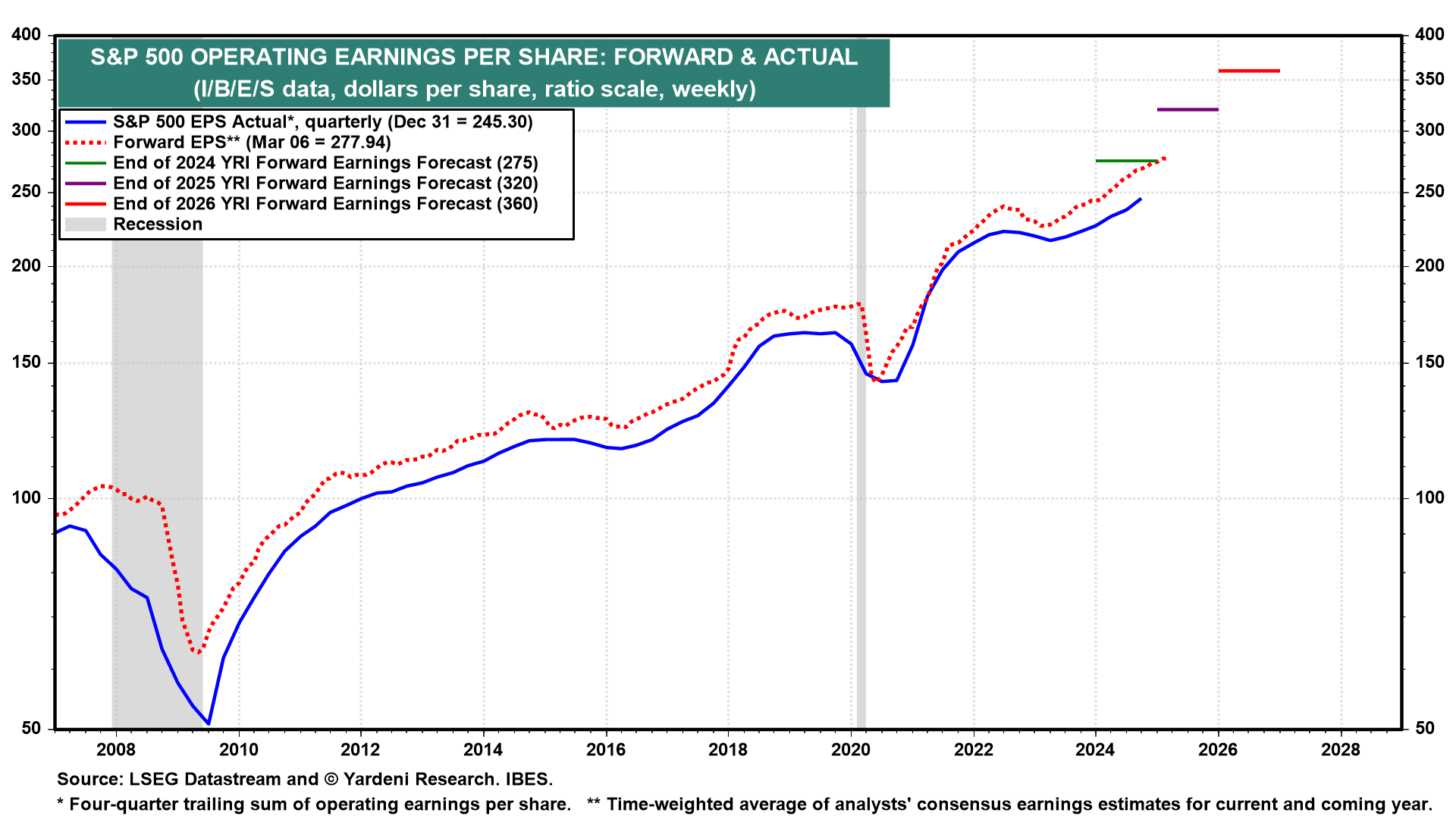

Today, we are blinking on the valuation multiple of the S&P 500. But for now, we are sticking with our strong estimates for S&P 500 companies’ aggregate earnings per share of $285 this year and $320 next year. We are still targeting forward earnings per share—i.e., the average of analysts’ consensus estimates for this year and next, time-weighted to represent the coming 12 months—of $320 at the end of this year and $360 at year-end 2026 (Fig. 11).

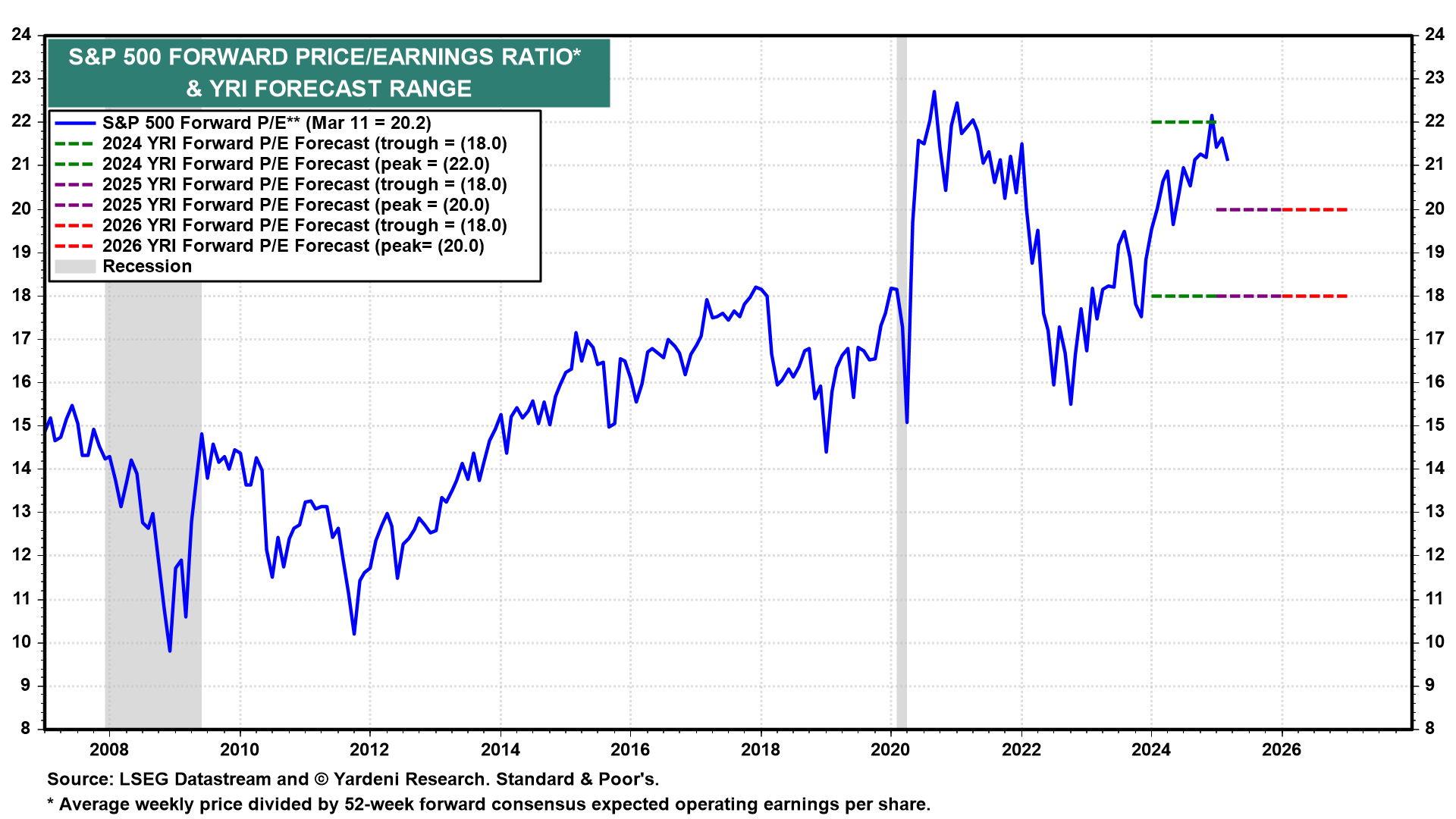

On the other hand, under the circumstances discussed above, we are lowering our forward P/E forecasts for the end of 2025 and 2026 to a range of 18-20, down from 18-22 (Fig. 12).

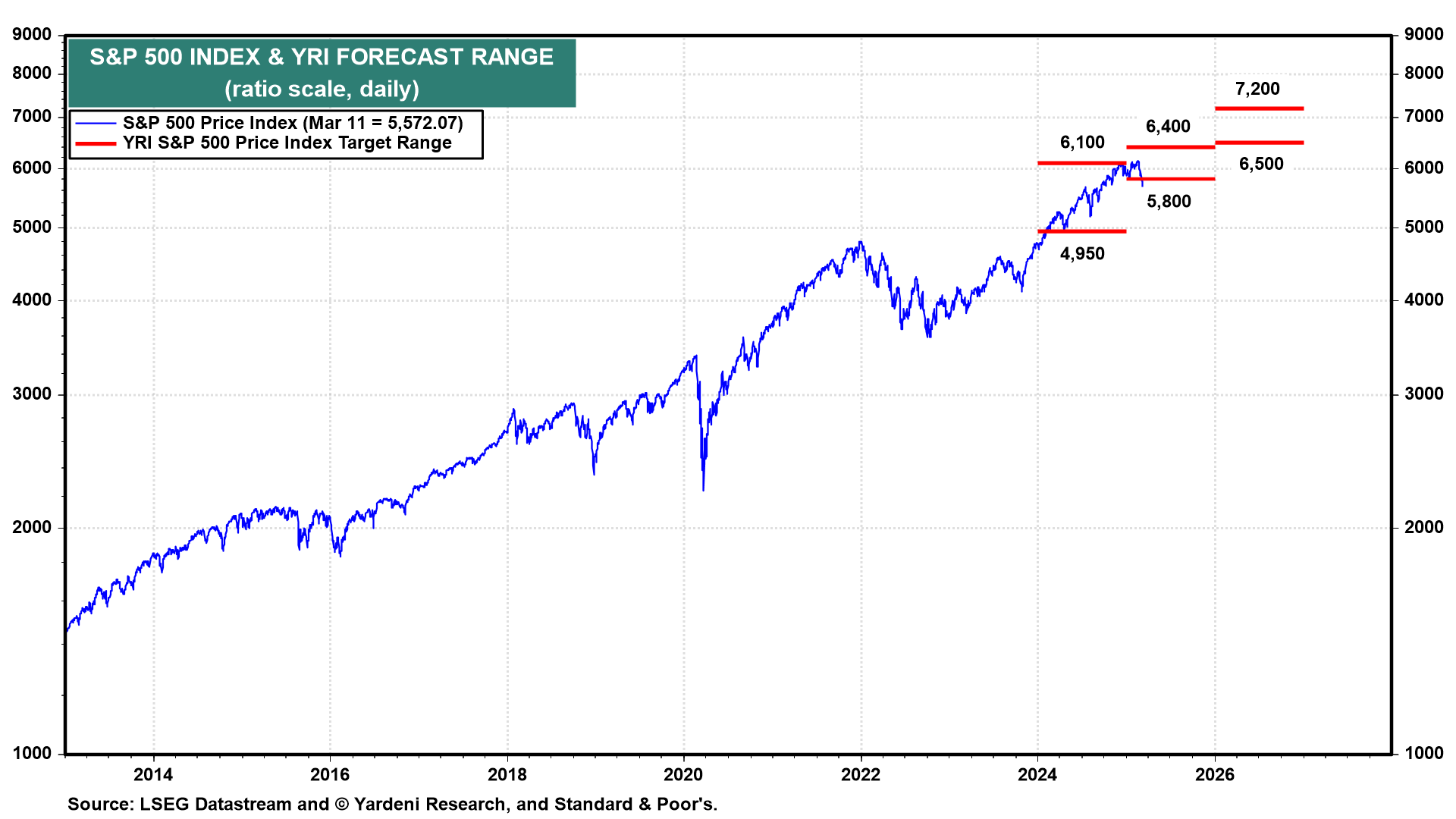

That lowers our best-case S&P 500 targets for the end of this year from 7000 to 6400 and for the end of next year from 8000 to 7200 (Fig. 13). The worst-case scenarios using the same forward earnings and the same 18 forward P/E assumptions would be 5800 and 6500 for this year and next year.

That’s if President Trump relents, as we expect he will to avoid a recession that would cost the Republicans their majorities in both houses of Congress in the mid-term elections in late 2026.