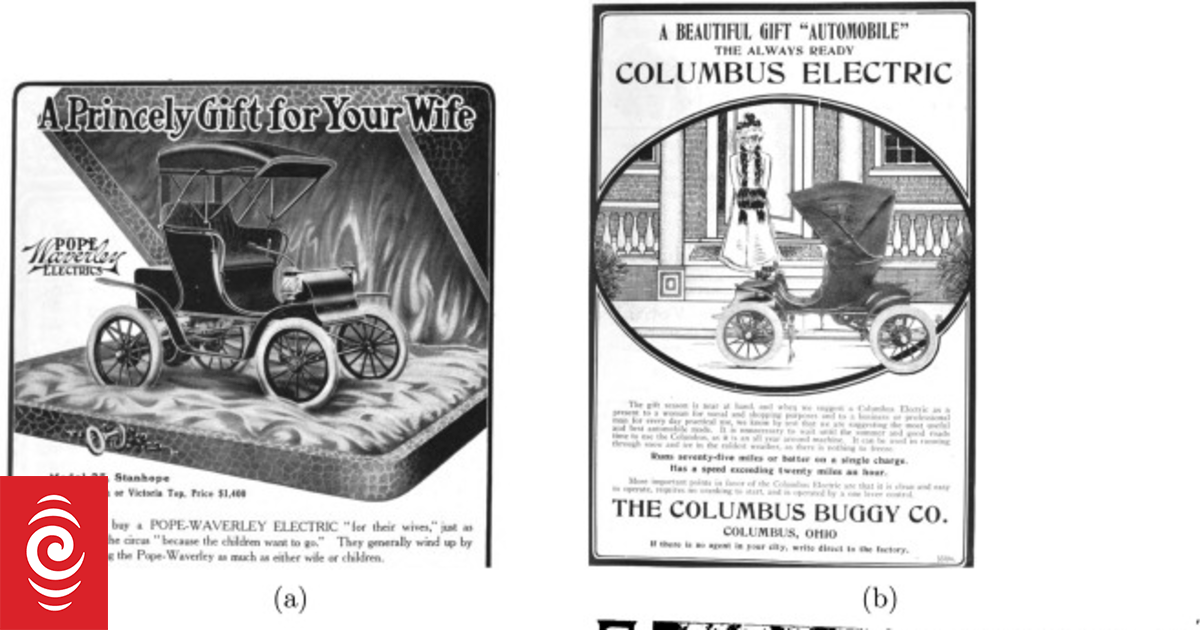

Early advertisements for electric cars.

Photo: Supplied / Josef Taalbi

There’s been a huge uptake of electric cars in recent years, and many of us would say they’re having their moment in the transport industry now.

But at the start of the 20th century, electric vehicles actually made up 40 percent of the market, while petrol cars were only at 20 percent (the other 40 percent was made up of steam-driven vehicles). Some electric cars even clocked speeds over 100km/h.

Economic historian and associate professor at Lund University, Josef Taalbi, has been researching this and spoke to Saturday Morning about how the petrol car came to conquer.

He explained the popularity of electric vehicles, or ‘horseless carriages’ as they were also called, began to dwindle in the 20th century.

“Where there weren’t electric grids, people or car producers would choose gasoline cars, and where there were electric grids, they would choose electric vehicles,” Taalbi said.

Economic historian and associate professor at Lund University Josef Taalbi.

Photo: Supplied

“The thing is that electricity was basically lacking in the beginning of the 20th century. There wasn’t enough, but it expanded quite quickly. So according to our estimates, if electricity would have started developing 15 years earlier than it actually did in the US, almost all car producers would actually have chosen electric cars instead of gasoline cars, especially in the large cities.”

Early electric cars could have a range of 135km, and were cheaper to drive than their petrol counterparts. But as the advantages of petrol cars became more apparent, producers stopped developing the electric car battery.

“So we could have had a completely different world. And that is a bit interesting to think about, of course.”

The lack of power infrastructure was not the only thing that led to the electric vehicle’s demise – by the 1910s, companies started marketing their electric vehicles towards women as “sitting rooms on wheels”, in a bid to increase sales as car producers leant towards gasoline-powered vehicles instead.

“So they were basically marketed towards women in order to sell what was then perceived as the limitations of the cars in terms of range and in terms of speed, because women were perceived of having less mobility needs than men.”

Another factor was the electric car’s push-start: unlike the petrol vehicles of the day, they did not require a crank.

In the 1910s, car manufacturers began marketing electric vehicles towards women.

Photo: Supplied / Josef Taalbi

“The fact that you had to crank-start the gasoline car was construed as masculine,” Taalbi said.

“To sort of crank-start the car was a very, very heavy job so that was something that played into the gender roles at that day and age. Whereas electric cars were clean and they were simple, and they were very simple to drive, and that was something that was viewed as sort of playing into femininity.”

Unfortunately, this marketing angle would eventually have the opposite effect – as men wanted to avoid buying cars they perceived as feminine, while women “very likely started viewing electric vehicles as limiting, rather than sort of liberating”.

What if it had been the other way round?

Taalbi is even-handed about the idea that widespread use of the electric vehicle might have been the answer to the world’s environmental and climate problems.

“If you do some calculations, which I and my colleague have done, you would see that the CO2 emissions that we could have saved already in the 1920s would have amounted to some tens of millions of tons,” he said.

“But then one should be a little bit critical because of course, electric cars rely on the battery, and the battery, well, you can have nickel, you can have iron, so that also has environmental consequences.

“I don’t want to paint electric cars in an unrealistic light… they could have also had environmental consequences. I mean this speaks to the notion that technologies can be solutions to problems, but they often also cause problems, and that’s why it’s important not to view one single technology as a sort of panacea or a global solution.

“We can understand the benefits of technology in a short-term perspective. We don’t really know the long-term consequences.

“Technological development needs to take place in a way that ensures that long-term interests are also brought into the discussion.”

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.