As global competition intensifies, China’s dominance over rare earth elements has become one of the most potent tools in its geopolitical arsenal. By controlling the extraction, refining, and global supply chains of these critical materials, Beijing holds extraordinary leverage over key sectors like defence, clean energy, AI, and electric vehicles, forcing the West into a high-stakes race to reduce its dangerous dependency.

Introduction

In the intricate web of global trade, few commodities hold as much strategic weight as rare earth elements (REEs), 17 metallic elements that, despite being relatively abundant in nature, are extremely difficult and costly to extract and refine. Their unique properties make them indispensable to a vast array of advanced technologies, from smartphones and electric vehicles to renewable energy, AI processors, and sophisticated defence systems.

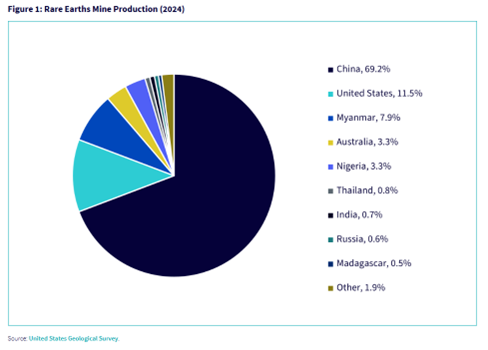

As China has methodically secured near-total control over the rare earth supply chain, controlling around 70% of global production and nearly 90% of refining capacity, these elements have become a powerful lever in its escalating economic rivalry with the United States.

With rare earths at the centre of critical industries and national security concerns, China’s dominance positions it as a formidable player in the broader contest for global influence, with profound implications for global supply chains, financial markets, and long-term investment risks.

The Strategic Importance of Rare Earths

Rare earth elements serve as the backbone of modern technological advancement. Despite representing a small market in absolute dollar terms, indeed the global rare earth market size was valued at $792.52 million in 2024 and is projected to reach from $863.38 million in 2025 to $1024.64 million by 2033, exhibiting a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of 8.94% during the forecast period, their economic significance far exceeds their market size due to their irreplaceable role in value-added industries.

For instance, neodymium and praseodymium are critical for manufacturing permanent magnets used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, and precision-guided weapons. Dysprosium and terbium enhance these magnets’ performance under extreme temperatures, vital for both military and aerospace applications.

The defence sector’s reliance on rare earths is particularly acute. Modern fighter jets, missile guidance systems, radar, and stealth technology all depend on specialised rare earth components. For example, a single F-35 fighter jet contains nearly 417 kilograms—approximately 920 pounds—of rare earth materials. Similarly, Virginia-class submarines, missile defence systems like THAAD, and advanced satellites all require specialised rare earth alloys to ensure functionality and reliability.

The rapid growth of renewable energy technologies, especially wind turbines and electric vehicles, has dramatically increased demand for high-performance rare earth magnets. Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, which contain multiple rare earth elements, are crucial for the lightweight, high-efficiency motors that underpin green energy transitions.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that demand for rare earth elements used in clean energy technologies could quadruple by 2040 under ambitious global climate targets.

Beyond the defence and energy sectors, rare earths are also central to consumer electronics and emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, 5G infrastructure, and quantum computing. High-end smartphones, medical imaging equipment, lasers, fibre optic cables, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment all require precise quantities of these elements. As such, disruptions in rare earth supply chains have a multiplier effect, affecting many global industries simultaneously.

This combination of essentiality and scarcity creates an asymmetric risk exposure for economies heavily dependent on stable access to these resources. Unlike commodities like oil or wheat, rare earths have few viable substitutes, and developing alternative supply chains requires years of investment, regulatory approval, and advanced technical expertise.

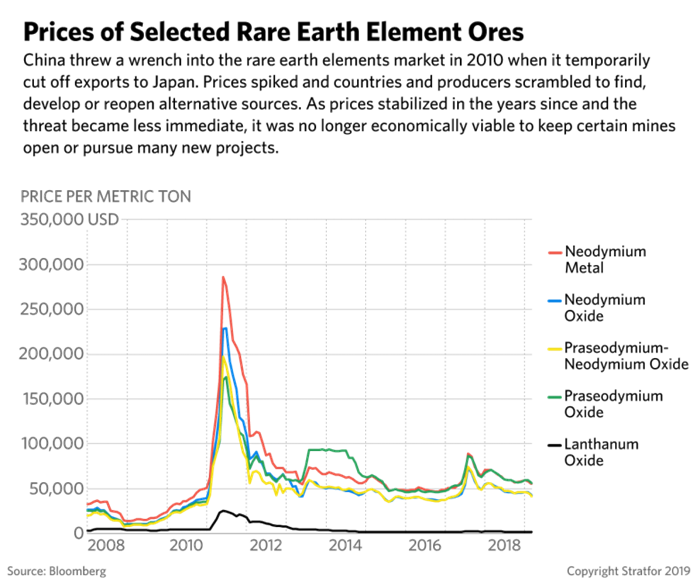

For financial markets, this fragility translates into supply chain vulnerabilities, pricing volatility, and potential geopolitical risk premiums embedded into equities exposed to technology, defence, and renewable energy sectors. For example, when China briefly restricted rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 following a diplomatic dispute, prices of some rare earth elements skyrocketed within months, triggering significant market volatility.

China’s strategic control of rare earths thus gives it an outsized influence relative to the sector’s financial footprint. It is not just about raw materials, but about who controls the nodes of the global value chain where advanced refining, separation, and processing occur. Today, roughly 85-90% of the world’s rare earth refining capacity and around 70% of total production are in China.

This leverage allows Beijing to influence global manufacturing priorities, pricing power, and even diplomatic negotiations in ways that extend far beyond simple trade balances. For investors, this dominance represents both a geopolitical risk factor and a potential investment opportunity, as companies involved in rare earth exploration, recycling, and alternative supply chains outside of China attract increasing capital amid efforts to diversify global production.

“The Middle East Has Oil; China Has Rare Earths.” ~ Deng Xiaoping

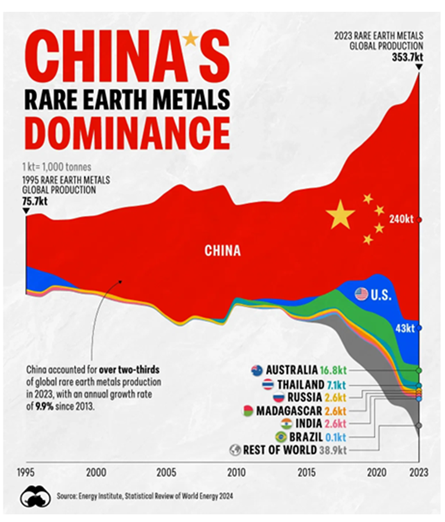

The rise of China as the dominant force in the rare earth market reflects a textbook case of long-term industrial strategy, executed with precision and patience over several decades. While many Western economies shifted their focus toward high-value industries and offshored heavy manufacturing, Beijing took a contrarian view, recognising early on the critical importance of securing the entire supply chain of strategic materials like rare earths.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, China identified rare earths as a national priority. Led by Xu Guangxian, the father of China’s rare earth industry, and backed by the newly formed Chinese Society of Rare Earth, China poured vast state resources into mining, refining, and separation. While these industries posed serious environmental challenges, the Chinese government tolerated pollution in exchange for strategic positioning, allowing companies to scale rapidly without the regulations faced by their Western counterparts.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, China combined state subsidies, cheap labour, and lax environmental oversight to dominate global rare earth production. Western countries, focusing on cost efficiencies and rising environmental standards, increasingly outsourced refining to Chinese plants. This effectively hollowed out domestic rare earth industries in the US, Japan, and Europe, while locking global supply chains into Chinese control.

Crucially, China did not stop at raw extraction, in which they also have a major advantage, as they account for roughly 70% of global production. The government invested heavily in mastering the highly complex refining and separation processes that transform raw ores into high-purity oxides and specialised alloys.

Today, more than 85% of rare earth refining capacity globally is concentrated in China. This vertical integration allows Beijing to control not only prices but also technological expertise, making it extremely difficult for new entrants to compete.

Rare Earths as Beijing’s Lever

By mid-2025, China’s rare earth strategy has entered a much sharper phase, blending calculated export pressure, financial leverage, and data extraction tactics. Far from relying on blanket bans, Beijing applies dynamic restrictions that disrupt global supply chains while keeping diplomatic channels technically open.

According to Chinese customs data reported by Bloomberg, rare earth exports to the US dropped 37% in April 2025, while rare earth magnet sales fell even more dramatically: 58% to the US and 51% globally.

The auto sector felt the shock first. By May, Ford, GM, and European manufacturers began reporting acute bottlenecks after exhausting their stockpiles of rare earth magnets. Mark Smith, CEO of US-based NioCorp, captured industry sentiment bluntly: “The automobile industry is now using words like panic, they’re talking about shutting down production lines.”

A temporary partial recovery followed high-stakes talks in Geneva between US and Chinese officials, with global rare earth exports rebounding 23% in May. Even with this slight reprieve, volumes remain well below 2024 levels, and the spectre of renewed disruption continues to rattle financial markets.

More alarmingly for Western firms operating in China, Beijing has begun demanding sensitive commercial information, including customer lists, pricing data, and production details, as a precondition for receiving rare earth licenses.

As the Financial Times reported, several European and US firms face mounting pressure to disclose strategic trade secrets in exchange for maintaining supply access. This emerging tactic effectively weaponises China’s regulatory authority to extract corporate intelligence while expanding its influence across downstream industries.

Simultaneously, Chinese sovereign wealth funds and state-backed conglomerates continue acquiring stakes in foreign rare earth mining projects, advanced magnet firms, and downstream processing facilities. By tying export permits to equity participation, China amplifies its grip not only on raw material flows but also on corporate ownership structures across the rare earth value chain.

Yet this intensification carries long-term risks for Beijing. As The National Interest cautioned, overplaying this hand may force the US, EU, Australia, and Canada to commit fully to the costly process of building domestic mining, refining, recycling, and substitution capabilities. If this accelerated diversification succeeds, Beijing’s current dominance could face serious erosion over the next decade.

For now, however, China’s 2025 rare earth campaign remains an exquisitely tuned mix of coercion, finance, and diplomacy. It is not simply a raw commodity squeeze—it is the careful orchestration of global supply dependencies, capital flows, and corporate vulnerabilities. Rare earths have become not just minerals but instruments in the grand chessboard of 21st-century economic statecraft.

Conclusion

The rare earth saga epitomises the evolving complexity of 21st-century geopolitics, where raw materials are no longer mere industrial inputs but highly strategic economic and diplomatic instruments.

China’s unparalleled dominance over mining, refining, and downstream processing has given it an extraordinary lever in its contest with the United States and the broader Western bloc. Through a finely tuned mixture of selective export restrictions, financial asset grabs, regulatory coercion, and corporate data extraction, Beijing has elevated rare earths from obscure commodities into powerful tools of global statecraft.

However, this asymmetric advantage is not without its vulnerabilities. Each aggressive move by China further incentivises Western nations to accelerate efforts at diversification, supply chain independence, and technology substitution. The financialisation of rare earths, evidenced by sharp volatility in equities and commodities markets, reflects not only speculative excitement but also the fragility of an overly concentrated global supply system.