If residential mortgages get messy, banks are largely off the hook this time.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

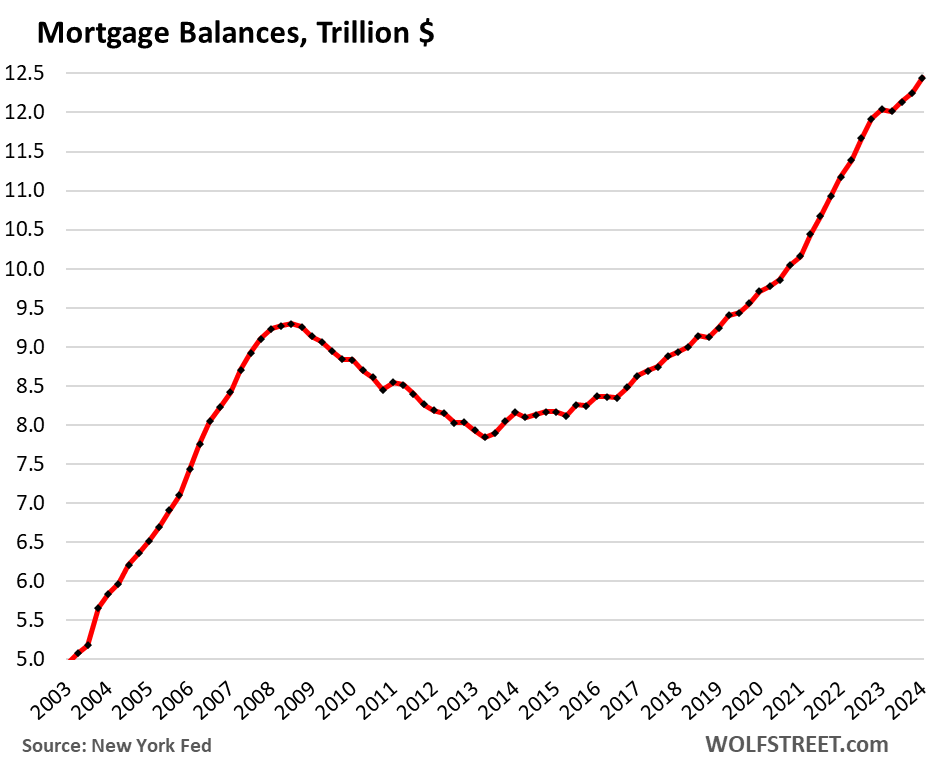

Mortgage balances rose by $190 billion, or by 1.6% in Q1 from Q4, and by 3.3% year-over-year, to a record of $12.4 trillion, according to the Household Debt and Credit Report from the New York Fed. Mortgages account for 80% of total household debt.

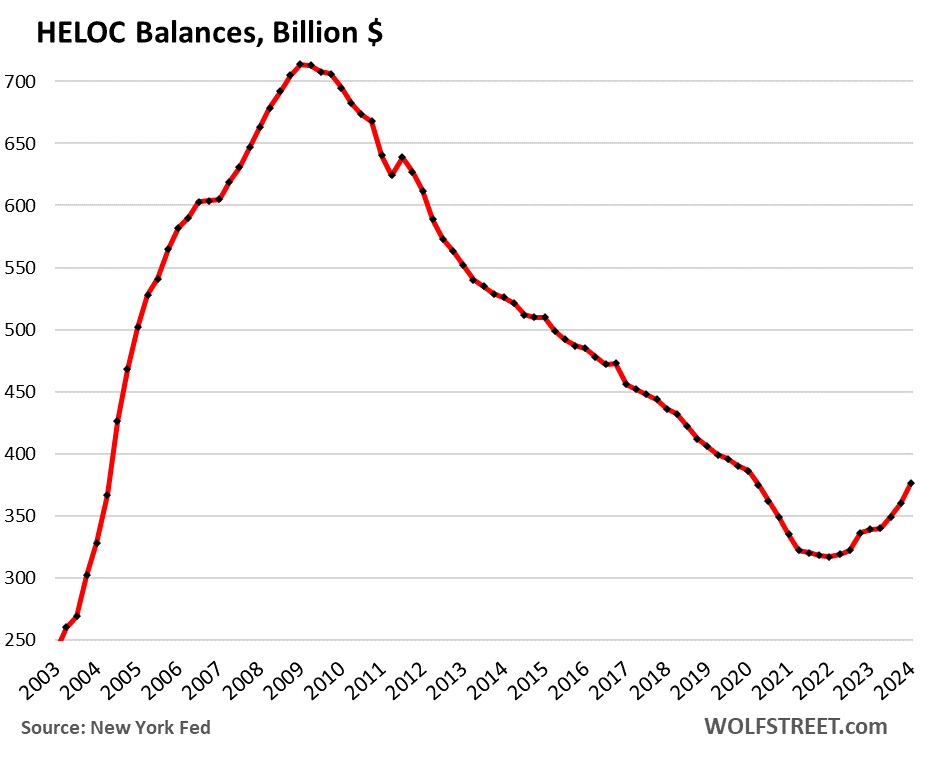

But HELOCs (home equity lines of credit) are rising from the ashes. Balances jumped by 4.4% for the quarter, and by 10.9% year-over-year – more in a moment.

In terms of mortgage balances, the relatively small 3.3% year-over-year increase is the result of several factors that pull in different directions: Still sky-high home prices that require larger mortgages; purchases of existing homes that have plunged; mortgage origination volume that has plunged; while purchases of new houses have held up, as prices have dropped 18%, and buyers are financing less expensive new houses. And a big part of homeowners with 3% mortgages are not selling, and they’re not buying either, and so they’re not paying off their 3% mortgages, and they’re not getting bigger new mortgages to buy more expensive homes:

But HELOC balances are rising from the ashes.

HELOC balances jumped by $16 billion, or by 4.4% in Q1 from Q4, and by 10.9% year-over-year, to $376 billion. Despite the recent surge, HELOC balances remain historically low after 13 years of incessant declines.

HELOCs are a way for homeowners to turn their own money buried in their home into useable cash. But to get to their own money, they have to pay Wall Street fees and interest on it.

The 7% mortgage rates have made cash-out refis – which refinances the mortgage plus the cash-out at this high rate – too expensive, and refi volume has collapsed. A HELOC may come with interest rates of 9%, or whatever, but it applies only to the amount drawn on the line of credit, and not the mortgage which continues at 3%.

Second-lien mortgages accomplish the same as a HELOC, but have fixed payments over a fixed term. They too are an expensive way for homeowners to turn their own money buried in their home into useable cash as Wall Street will exact its pound of flesh.

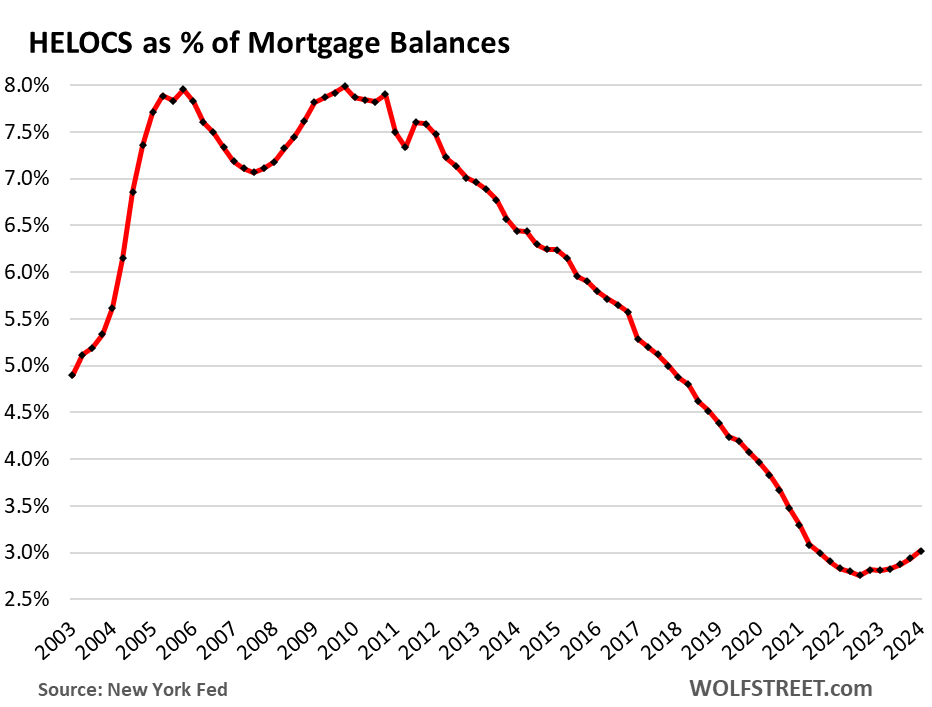

HELOCs are still a tiny portion of the housing debt, accounting for just 3.0% of total mortgage balances in Q1, having barely moved up from the historic low of 2.8% in Q3 2022. Once upon a time in 2005 through 2012, HELOCs amounted to 7-8% of mortgage balances:

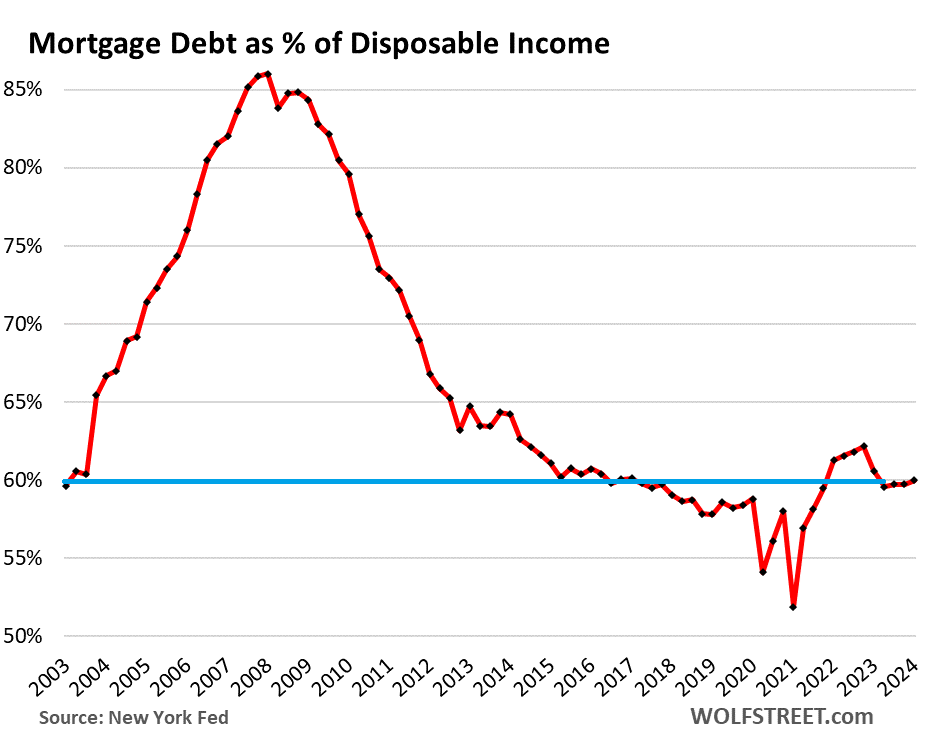

The burden of mortgage debt.

To measure the burden of mortgage debt on households, we can compare mortgage balances to disposable income, which is what households have left over from their total income, after payroll taxes and social insurance payments, to deal with their costs of living and service their debts.

Disposable income is income from all sources but not capital gains (wages, interest, dividends, rentals, farm income, small business income, transfer payments from the government, etc.), minus taxes and social insurance payments. And disposable income has surged (data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis):

- Quarter over quarter: +1.1%

- Year-over-year: +4.3%

- Since 2019: +26.7%.

The ratio of mortgage balances to disposable income has been roughly flat for the past four quarters at around 60%. Note how the ratio dropped in 2022 and Q1 2023, as wages surged. Recently, wage growth has slowed, and the ratio has stabilized near historically low levels:

Delinquencies haven’t normalized yet.

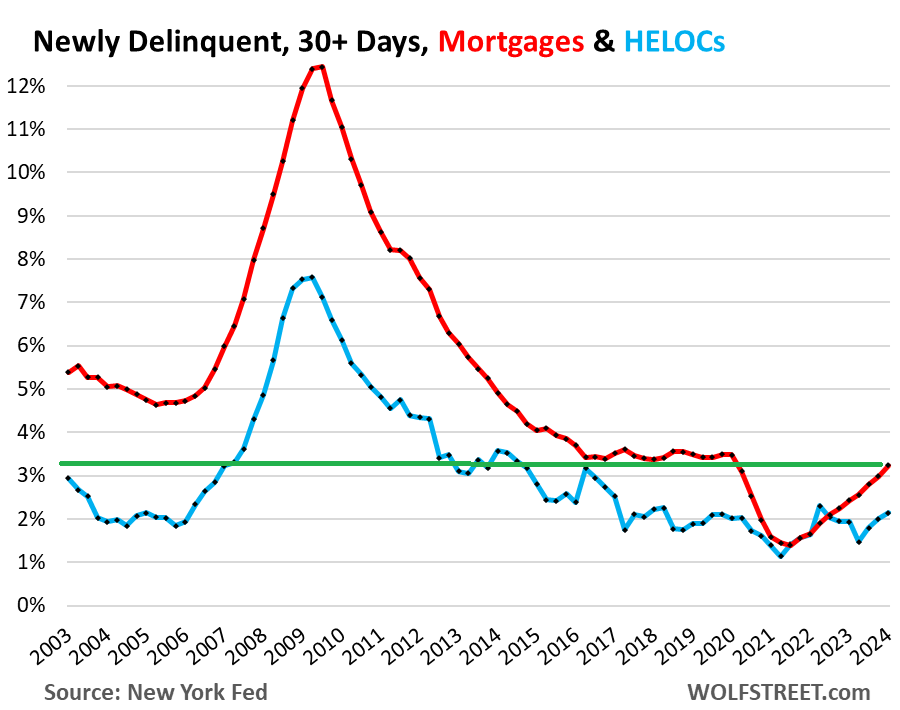

Transitioning into delinquency: Mortgage balances that were delinquent by 30 days or more ticked up to 3.2% of total balances — still lower than any time before the pandemic (red line in the chart below).

HELOC balances that were delinquent by 30 days or more ticked up to 2.1% (blue line).

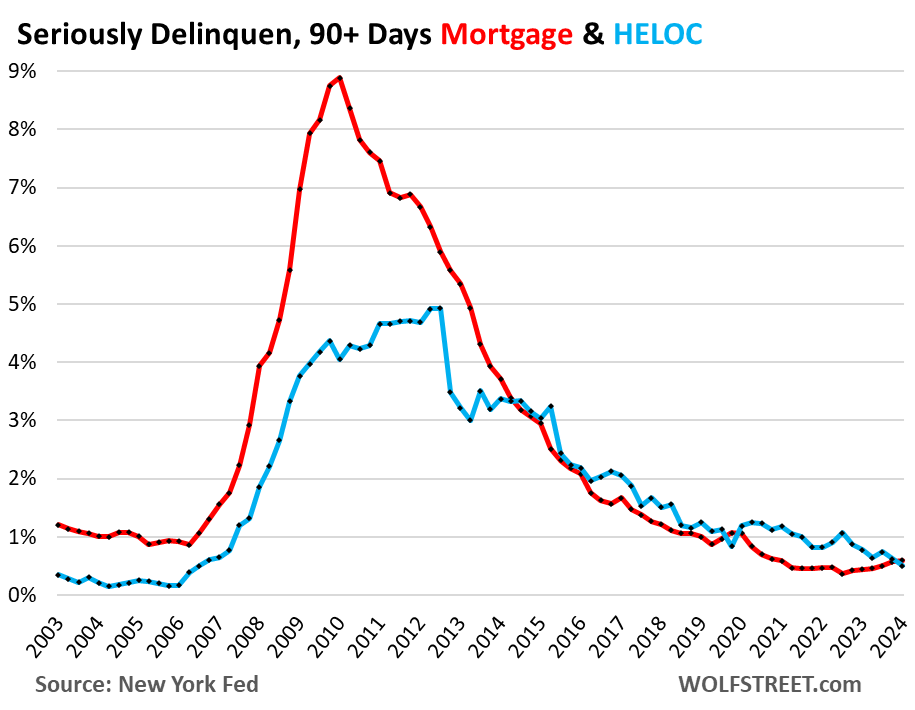

Serious delinquency: Mortgage balances that were 90 days or more delinquent edged up to 0.6%, compared to 1.0% and higher before the pandemic (red line in the chart below).

HELOC balances that were 90 days or more delinquent dipped to 0.5%, the lowest since 2006 (blue line).

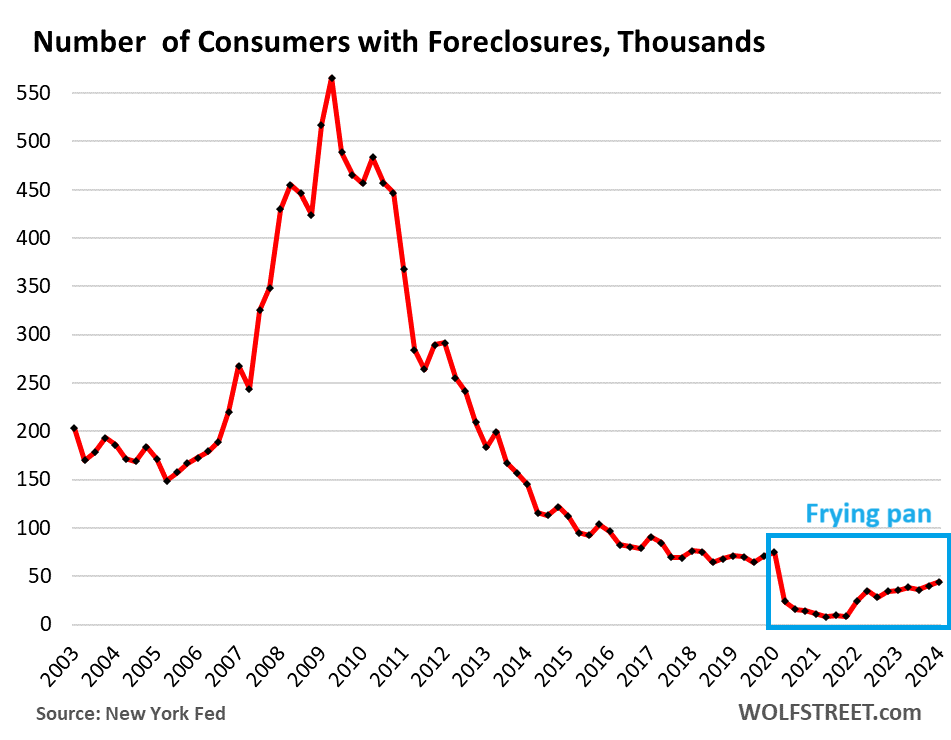

Foreclosures in a post-pandemic frying-pan pattern.

During the pandemic, with mortgage forbearance and foreclosure bans in effect, the number of consumers with foreclosures plunged to near zero. They have risen since then but remain far below the Good Times lows before the pandemic.

In Q1, there were 44,200 consumers with foreclosures, compared to 65,000 to 90,000 in the years 2017 through 2019. In other words, they’re not even normalizing yet. The post-pandemic frying-pan pattern has cropped up in a number of other data as well:

Foreclosures won’t be a problem until…

…home prices sag and people lose their jobs. That’s the short version.

Homeowners who purchased their homes more than two years ago and didn’t cash-out-refi have lots of equity in their homes as home prices have surged in the years through mid-2022. And that’s the vast majority of homeowners. But more recent homebuyers can get into serious trouble fairly quickly.

If a homeowner with a lot of equity cannot make the mortgage payments because they lost their job or had a medical emergency, they can sell the home, pay off the mortgage with the proceeds, and have some cash left.

If unemployment surges and over a year’s time a million homeowners cannot make their payment anymore, they can sell their home, pay off their mortgage, and go on.

The problem arises when home prices plunge to multi-year lows, and suddenly a larger portion of homeowners are underwater. Being underwater for a homeowner is no biggie as long as they don’t have to sell. They just hang tight, quit looking at Zillow every day, and life goes on.

But if they have to sell, it gets complicated. If lots of people lose their jobs and can no longer make the mortgage payments, and have to sell, then it gets a little messy because it drives down prices even further. The result will be that homes will become more plentiful on the market, and more affordable to buy, which would be welcome by lots of people and would solve a crisis.

Banks are largely off the hook this time.

The mess would mostly hit taxpayers, who now are on the hook for a large majority of the mortgages – not banks. The exception are HELOCs; the government has not yet taken them under its wings. But HELOC balances are still small.

Banks have relatively few mortgages on their books; they sell most of them off to government entities which turn them into government-backed MBS and sell them to investors. Banks not being on the hook for the biggest part of the mortgages is one of the fundamental changes since the mortgage crisis. So this time, the Fed can let the housing market do its thing without having to worry about the financial system collapsing under the weight of imploding mortgages. The financial system might get tripped up by other problems, but not residential mortgages.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()